Bible connection

The Spirit of God came on Azariah son of Oded. He went out to meet Asa and said to him, “Listen to me, Asa and all Judah and Benjamin. The Lord is with you when you are with him. If you seek him, he will be found by you, but if you forsake him, he will forsake you. For a long time Israel was without the true God, without a priest to teach and without the law. But in their distress they turned to the Lord, the God of Israel, and sought him, and he was found by them. In those days it was not safe to travel about, for all the inhabitants of the lands were in great turmoil. One nation was being crushed by another and one city by another, because God was troubling them with every kind of distress. But as for you, be strong and do not give up, for your work will be rewarded.” — 2 Chronicles 15:1-7

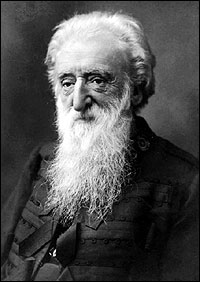

All about Johnny Cash (1932-2003)

John R. “Johnny” Cash born February 26, 1932. He is widely considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century and is one of the best-selling music artists of all time, having sold more than 90 million records worldwide. Although primarily remembered as a country music icon, his genre-spanning songs and sound embraced rock and roll, rockabilly, blues, folk, and gospel. His crossover appeal won Cash the rare honor of being inducted into the Country Music, Rock and Roll, and Gospel Music Halls of Fame.

Cash was known for his deep, calm bass-baritone voice, a rebelliousness coupled with an increasingly somber and humble demeanor, free prison concerts, and his trademark attire, which earned him the nickname “The Man in Black.” He traditionally began his concerts with the simple “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash,” followed by his signature Folsom Prison Blues.

Much of Cash’s music echoed themes of sorrow, moral tribulation and redemption, especially in later life. During the last stage of his career, Cash covered songs by several late 20th century rock artists, most notably Hurt by Nine Inch Nails (video below).

Cash was raised by his parents as a Southern Baptist. He was baptized in 1944 in the Tyronza River as a member of the Central Baptist Church of Dyess, Arkansas.

A troubled but devout Christian, Cash has been characterized as a “lens through which to view American contradictions and challenges.” He wrote a Christian novel, Man in White, which showcases his theological studies. It is is a portrait of six pivotal years in the life of the apostle, Paul. In the introduction Cash writes about a reporter who, once tried to paint him into a corner, baiting him to acknowledge a single denominational persuasion at the center of his heart. Finally, Cash laid down the law: “I—as a believer that Jesus of Nazareth, a Jew, the Christ of the Greeks, was the Anointed One of God (born of the seed of David, upon faith as Abraham has faith, and it was accounted to him for righteousness)—am grafted onto the true vine, and am one of the heirs of God’s covenant with Israel….I’m a Christian. Don’t put me in another box.”

He made a spoken word recording of the entire New King James Version of the New Testament. Cash declared he was “the biggest sinner of them all”, and viewed himself overall as a complicated and contradictory man. Accordingly, Cash is said to have “contained multitudes,” and has been deemed “the philosopher-prince of American country music.”

Cash’s daughter, singer-songwriter Rosanne Cash, once pointed out that “My father was raised a Baptist, but he has the soul of a mystic. He’s a profoundly spiritual man, but he readily admits to a continual attraction for all seven deadly sins.”

“There’s nothing hypocritical about it,” Johnny Cash told Rolling Stone author Anthony DeCurtis. “There is a spiritual side to me that goes real deep, but I confess right up front that I’m the biggest sinner of them all.” To Cash, even his near deadly bout with drug addiction contained a crucial spiritual element. “I used drugs to escape, and they worked pretty well when I was younger. But they devastated me physically and emotionally—and spiritually … [they put me] in such a low state that I couldn’t communicate with God. There’s no lonelier place to be. I was separated from God, and I wasn’t even trying to call on him. I knew that there was no line of communication. But he came back. And I came back.”

“Being a Christian isn’t for sissies,” Cash said once. “It takes a real man to live for God—a lot more man than to live for the devil, you know? If you really want to live right these days, you gotta be tough.”

What’s more, he was intimately aware of the hard truths about living God’s way: “If you’re going to be a Christian, you’re going to change. You’re going to lose some old friends, not because you want to, but because you need to.”

”I’m thrilled to death with life,” he told Larry King during an interview. “Life is—the way God has given it to me—was just a platter. A golden platter of life laid out there for me. It’s been beautiful.”

“I don’t give up … and it’s not out of frustration and desperation that I say ‘I don’t give up.’ I don’t give up because I don’t give up. I don’t believe in it.”

What do we do with this?

Johnny Cash was a celebrity, which usually equals trouble. He had plenty of trouble. But he also had plenty of conviction that lasted his whole life. In many ways he is an “everyman” who stubbornly tried to do his best, often standing with the downtrodden. Notably, he risked his career early on to speak out on behalf of Native Americans. He used his capabilities and his notoriety for more than his own pleasure and profit.

Cash sang these words in one of his last songs, “Ain’t No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down,” recorded in 2003 in the final months of his life and released posthumously in 2010: “When I hear that trumpet sound, I’m gonna rise right out of the ground. Ain’t no grave can hold my body down. … Well, meet me, Jesus, meet me. Meet me in the middle of the air. And if these wings don’t fail me, I will meet You anywhere.”

Can you sing that?

If you can’t be held down, what can you do?