Bible connection

Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothes? Look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they? Can any one of you by worrying add a single hour to your life. (Matthew 6:25-7)

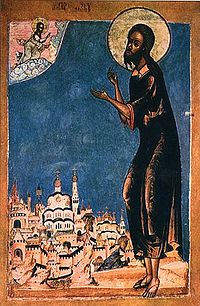

All about Francis of Assisi (1181-1226)

Francis of Assisi was born around 1181 and died in his forties on October 3, 1226 (but his feast day is Oct. 4 for various reasons). He was born as John Francis (son of) Bernard (Giovanni Francesco di Bernardone) to a wealthy cloth merchant. He enjoyed a luxurious and wordly lifestyle in his youth.

He fought as a soldier for Assisi. But while at war, he had the first of many experiences that called him to a life of poverty, community and restoration of the church. Shortly after he returned to Assisi after a battle, he began to give witness of his newfound Love in the streets. Soon a group of young men were travelling with him. His influence generated the Franciscan order, the Order of St. Clare and the Third Order Franciscans.

Francis impacted thousands of people during his relatively short ministry. He was seen as a beacon of light during a period of corruption and darkness in the Church. He is still highly regarded and still gathering followers today.

Here is part of the biography of his early years from the Catholic Encyclopedia

Not long after his return to Assisi, whilst Francis was praying before an ancient crucifix in the forsaken wayside chapel of St. Damian’s below the town, he heard a voice saying: “Go, Francis, and repair my house, which as you see is falling into ruin.” Taking this behest literally, as referring to the ruinous church wherein he knelt, Francis went to his father’s shop, impulsively bundled together a load of coloured drapery, and mounting his horse hastened to Foligno, then a mart of some importance, and there sold both horse and stuff to procure the money needful for the restoration of St. Damian’s. When, however, the poor priest who officiated there refused to receive the gold thus gotten, Francis flung it from him disdainfully. The elder Bernardone, a most niggardly man, was incensed beyond measure at his son’s conduct, and Francis, to avert his father’s wrath, hid himself in a cave near St. Damian’s for a whole month. When he emerged from this place of concealment and returned to the town, emaciated with hunger and squalid with dirt, Francis was followed by a hooting rabble, pelted with mud and stones, and otherwise mocked as a madman. Finally, he was dragged home by his father, beaten, bound, and locked in a dark closet.

Freed by his mother during Bernardone’s absence, Francis returned at once to St. Damian’s, where he found a shelter with the officiating priest, but he was soon cited before the city consuls by his father. The latter, not content with having recovered the scattered gold from St. Damian’s, sought also to force his son to forego his inheritance. This Francis was only too eager to do; he declared, however, that since he had entered the service of God he was no longer under civil jurisdiction. Having therefore been taken before the bishop, Francis stripped himself of the very clothes he wore, and gave them to his father, saying: “Hitherto I have called you my father on earth; henceforth I desire to say only ‘Our Father who art in Heaven’.” Then and there, as Dante sings, were solemnized Francis’s nuptials with his beloved spouse, the Lady Poverty, under which name, in the mystical language afterwards so familiar to him, he comprehended the total surrender of all worldly goods, honours, and privileges. And now Francis wandered forth into the hills behind Assisi, improvising hymns of praise as he went. “I am the herald of the great King”, he declared in answer to some robbers, who thereupon despoiled him of all he had and threw him scornfully in a snow drift. Naked and half frozen, Francis crawled to a neighbouring monastery and there worked for a time as a scullion. At Gubbio, whither he went next, Francis obtained from a friend the cloak, girdle, and staff of a pilgrim as an alms. Returning to Assisi, he traversed the city begging stones for the restoration of St. Damian’s. These he carried to the old chapel, set in place himself, and so at length rebuilt it.

The Little Flowers of St. Francis sealed the image of Francis which was ultimately passed down. The order went through a predictable fracturing after he died. The original spirit was suppressed by the church and by members who wanted more conformity to established monastic practices. The Little Flowers, compiled at the end of the 1300’s, collects some tales that were stashed in attics or hidden from the authorities and included some new stories by a series of authors. Some of your favorite stories come from this book (free to read online) and from the Giotto paintings in the Basilica in Assisi.

More

Biography from the National Shrine in San Francisco. [link]

The movie: Brother Sun, Sister Moon trailer. [Buy or rent on Prime]. Francis is pictured as a representative of the spirit of the 70’s and the desire of young people for something greater than the corrupt institutions of church and state were offering.

Another movie: The Flowers of St. Francis, a 1950 film directed by Roberto Rossellini and co-written by Federico Fellini. This captures the spontaneous and joyful spirit that St Francis embodied. Here is another more recent Italian TV movie.

A fan mashed LeeAnn Womack with scenes from another movie Clare and Francis [or YouTube] to prove how his story is timeless. [link]

The newest of many favorite books about Francis: Francis of Assisi and His World, by Mark Galli, Eager to Love: The Alternative Way of Francis of Assisi, by Richard Rohr, The Road to Assisi by Jon Sweeny, Editor, The Last Christian by Adolf Holl.

Hans Kung, the great Catholic theologian, writes a great post about the first pope to take the name Francis.

What do we do with this?

“Francis’ all-night prayer, ‘Who are you, O God, and who am I?’ is probably a perfect prayer, because it is the most honest prayer we can offer.”—Richard Rohr in Eager to Love

Francis has become so well known for relating to animals that most people think of him as a birdbath. But he was a wild and creative radical, deliberately unsuited for a garden. He took the way of monasticism, added joy to it, the restoration of loving relationships, and connection to the earth. Consider his example of simplicity, submission, community, and his mission of building the church. How can you and we find our own version of a radical restoration of a deteriorating church?