Bible connection

Read Acts 2:14-21

In the last days, God says, I will pour out my Spirit on all people. Your sons and daughters will prophesy, your young men will see visions, your old men will dream dreams. Even on my servants, both men and women, I will pour out my Spirit in those days, and they will prophesy.

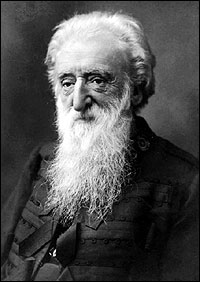

All about William J. Seymour (1870-1922)

William Joseph Seymour was born May 2, 1870 in Centerville, St. Mary’s Parish, Louisiana. His parents, Simon Seymour (also known as Simon Simon) and Phillis Salabar were both former slaves.

After Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, Seymour’s father enlisted in the Northern Army and served until the end of the Civil War. He may have contracted malaria or another tropical disease in the southern swamps. Simon never fully recovered.

William Seymour, the oldest in a large family, lived his early years in abject poverty. In 1896 the family’s possessions were listed as “one old bedstead, one old chair and one old mattress.” All of his mother’s personal property was valued at fifty-five cents. He also suffered the injustice and prejudice of the reconstruction south. Violence against freedman was common and groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorized southern Louisiana.

Many accounts of Seymour’s life say he was illiterate. This is not true. He attended a freedman school in Centerville and learned to read and write. In fact, his signature shows a good penmanship. Fleeing the poverty and oppression of life in southern Louisiana, Seymour left his home in early adulthood. He traveled and worked in Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and other states possibly including Missouri and Tennessee. He often worked as a waiter in big city hotels.

In Indianapolis, Seymour was converted in a Methodist Church. Soon, however, he joined the Church of God Reformation movement in Anderson, Indiana. At the time, the group was called “The Evening Light Saints.” While with this conservative Holiness group, Seymour was sanctified and called to preach. After a near fatal bout with smallpox, Seymour yielded to the call to ministry. The illness left him blind in one eye and scarred his face. For the rest of his life he wore a beard to hide the scars.

In 1905, Seymour was in Houston, Texas where he heard the Pentecostal message for the first time. He attended a Bible school conducted by Charles F. Parham. Parham was the founder of the Apostolic Faith Movement, a “tritheist,” also a member of the KKK and arrested as a pedophile (see Goff, James R. Jr. (1988). Fields White Unto Harvest: Charles F. Parham and the Missionary Origins of Pentecostalism. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-025-8). Because of the strict segregation laws of the times, Seymour was forced to sit outside the class room in the hall way. Nevertheless, he soon picked up all of Parham’s teaching, though not the gift of tongues. Parham and Seymour held joint meetings in Houston, with Seymour preaching to black audiences and Parham speaking to the white groups. Parham hoped to use Seymour to spread the Apostolic Faith message to the African-Americans in Texas. He and Seymour are both called the the father of the modern Pentecostal/Charismatic revival.

Neely Terry, a guest from Los Angeles met Seymour while he was preaching at a small church regularly pastored by Lucy Farrar (also spelled Farrow). Farrar was also an employee of Parham and was serving his family in Kansas. When Terry returned to Los Angeles, she persuaded the small Holiness church she attended to call Seymour to Los Angeles for a meeting. Her pastor, Julia Hutchinson, extended the invitation.

Seymour arrived in Los Angeles in February 1906. His early efforts to preach the Pentecostal message were rebuffed and he was locked out of the church. The leadership were suspicious of Seymour’s doctrine, but were especially concerned that he was preaching an experience that he had not received. He joined a prayer group in which his host was involved. On April 9, that man was baptized in the Holy Spirit with the evidence of speaking in other tongues. News of this event spread and a powerful outpouring followed. Over the next few days hundreds gathered. The streets were filled and Seymour preached from the porch. On April 12, three days after the initial outpouring, Seymour received his own Spirit baptism.

The group quickly outgrew the home. Seymour wrote:

In a short time God began to manifest His power and soon the building could not contain the people. Now the meetings continue all day and into the night and the fire is kindling all over the city and surrounding towns. Proud, well-dressed preachers come in to “investigate.” Soon their high looks are replaced with wonder, then conviction comes, and very often you will find them in a short time wallowing on the dirty floor, asking God to forgive them and make them as little children. ― The Azusa Papers

They found a bigger place at 312 Azusa Street. The mission had been built as an African Methodist Episcopal Church, but when the former tenants vacated, the upstairs sanctuary had been converted into apartments. A fire destroyed the pitched roof and it was replaced with a flat roof giving the 40 X 60 feet building the appearance of a square box. The unfinished downstairs with a low ceiling and dirt floor was used as a storage building and stable. This downstairs became the home of the Apostolic Faith Mission. Mismatched chairs and wooden planks were collected for seats and a prayer altar and two wooden crates covered by a cheap cloth became the pulpit.

On April 17, The Los Angeles Daily Times sent a reporter to the revival. In his article the next day, he lampooned the meeting and the pastor, calling the worshippers “a new sect of fanatics” and Seymour “an old exhorter.” He mocked their glossolalia as “weird babel of tongues.” However, his article was published on the same day as the great earthquake in San Francisco. Southern Californians, already gripped with fear, learned of a revival where doomsday prophecies were common.

Immediately an itinerate evangelist and Azusa Street participant published a tract about the earthquake. Thousands of the tracts, filled with end-time prophecies, were distributed. Soon, multitudes gathered at Azusa Street. One attendee said more than a thousand at a time would crowd onto the property. Hundreds would fill the little building; others would watch from the boardwalk; and, more would overflow into the dirt street.

With the help of a stenographer and editor the mission began to publish a newspaper, The Apostolic Faith. Seymour’s sermons were transcribed and printed, along with news of the meetings and the many missionaries that were being sent forth. Circulation for the little paper soon passed 50,000.

To Seymour, tongues was not the only message of Azusa Street: “Don’t go out of here talking about tongues: talk about Jesus,” he admonished.

An expression of the Spirit as notable as tongues was how blacks and whites were in one church at Azusa St. Seymour rejected racial barriers that plagued the Church at that time. Blacks and whites worked together in apparent harmony under the direction of a black pastor, a marvel in the days of Jim Crow segregation. One commentator said: “At Azusa Street, the color line was washed away in the Blood.”

What’s more, Seymour installed women as leaders (notably Lucy Farrow, a formerly enslaved woman and the niece of Frederick Douglass), which was almost universally opposed at the time. Seymour dreamed that Azusa Street was creating a new kind of church, one where a common experience in the Holy Spirit tore down old walls of racial, ethnic, and denominational differences.

Seymour quotes

- I can say, through the power of the Spirit that wherever God can get a people that will come together in one accord and one mind in the Word of God, the baptism of the Holy Ghost will fall upon them, like as at Cornelius’ house.

- So many today are worshiping in the mountains, big churches, stone and frame buildings. But Jesus teaches that salvation is not in these stone structures–not in the mountains—not in the hills, but in God.

- The Pentecostal power, when you sum it all up, is just more of God’s love. If it does not bring more love, it is simply a counterfeit.

- Many people today are sanctified, cleansed from all sin and perfectly consecrated to God, but they have never obeyed the Lord according to Acts 1, 4, 5, 8 and Luke 24: 39, for their real personal Pentecost, the enduement of power for service and work and for sealing unto the day of redemption. The baptism with the Holy Ghost is a free gift without repentance upon the sanctified, cleansed vessel. “Now He which stablisheth us with you in Christ, and hath anointed us, is God, who hath also sealed us, and given the earnest of the Spirit in our hearts” (2 Cor. 1: 21-22). I praise our God for the sealing of the Holy Spirit unto the day of redemption

More

Azusa Street Revival [link]

The Azusa Street Project movie (2006) [link]

More details in this bio [link]

A great theater note on the Gospel at Colonus enlightens us about ecstatic spiritual gifts. [link]

What do we do with this?

Seymour would probably simply ask us to consider his observation: “Many people today are sanctified, cleansed from all sin and perfectly consecrated to God, but they have never obeyed the Lord according to Acts 1, 4, 5, 8 and Luke 24: 39, for their real personal Pentecost, the enduement of power for service and work and for sealing unto the day of redemption.” What would you say about yourself?

The spiritual adventurer is the main character of his most well known fantasies, Phantastes and Lilith. There is a sequence at the end of Lilith which imagines heaven in such a beautiful, extended way it seems impossible. The protagonist wakes from his vision, reflects on his journey through the land of the dead to this beautiful heaven and wonders, “Was it a dream or a real journey and does that matter?”

The spiritual adventurer is the main character of his most well known fantasies, Phantastes and Lilith. There is a sequence at the end of Lilith which imagines heaven in such a beautiful, extended way it seems impossible. The protagonist wakes from his vision, reflects on his journey through the land of the dead to this beautiful heaven and wonders, “Was it a dream or a real journey and does that matter?”